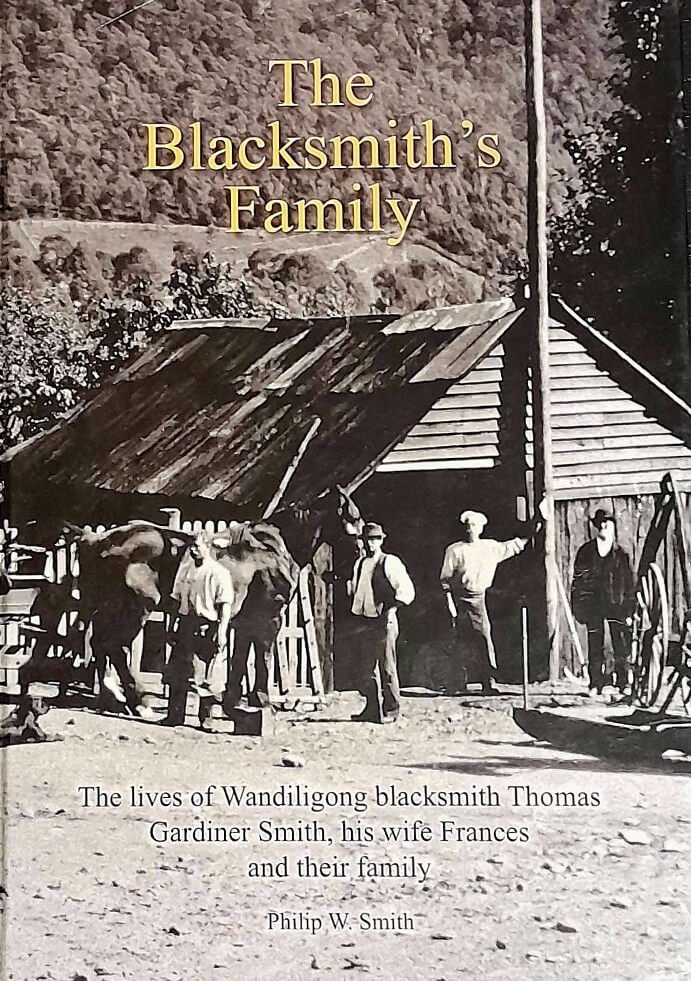

The Blacksmith’s Family by Philip Smith

The clipper Royal Family that landed Thomas and Frances Smith in Melbourne in February 1863.

It took me around 25 years to complete my first book, Merric Boyd and Murrumbeena: The Life of an artist in a Time and a Place. It took my father, Philip Smith, about the same number of years to research and write his family history, The Blacksmith’s Family. I really can’t remember when he started it, but it became his major focus and passion in the last decades of his life.

In his working life, Phil was a highly accomplished and successful chemical engineer who, with his partners David Piper and Graham Polkinghorn, established the exceedingly well regarded engineering firm, Process Design and Fabrication Pty Ltd. Phil had an engineer’s eye for detail. As a chemical engineer, he knew that the devil was always in the detail. As a retired engineer, he turned this ability to forensically focus on a task to carrying out research for his book. This filled his retired life with additional activity, because he was never bored and was always engaged with his family and other interests.

Thomas and Frances Smith around the 1870s.

Phil wrote The Blacksmith’s Family primarily for two reasons. The first was his attempt to discover the reason or reasons why his grandfather, Thomas Smith, a Wandiligong blacksmith, committed suicide in 1903. Wandiligong is a town in north-east Victoria and was established in the 1850s during the Victorian gold rush. Thomas and his wife Frances Smith (nee Hodgson) had emigrated to Australia from England in 1862 and settled there in 1863.

Phil’s research revealed several possible explanations for his suicide. These include mental illness, alcoholism, disappointment in his attempts to find gold, and a very public fall from grace, but he never conclusively resolved it. The reasons as to why people suicide are usually complex and multi-factorial, and likely Thomas’ death was no different.

The second reason for his book was to record the lives of three generations of his family in Wandiligong. The first generation was that of his grandparents’, Thomas and Frances. The second generation was his father’s. In his book, Phil called this ‘The Wandiligong Generation’. Thomas and Frances had six surviving children: Jane, George, Louis, Alma, Walter and Percy. They all grew up in Wandiligong, and over time left it, with the exception of Louis who stayed on as a town blacksmith following his father’s death. The second youngest of their children, Walter was Phil’s father.

The Blacksmith's Family contains an extraordinary collection of photographs of The Wandiligong Brass Band between the early 1890s and 1934. The sons of Thomas and Frances Smith played with the band for decades. This is the band circa 1890. At the back row and second from the left is Louis Smith, while Albert Smith is second from the right in the same row. At the far left is Percy Smith.

The Wandiligong Brass Band circa 1892. At the far left is Walter Smith, in the back row and centre is Albert Smith, and in the front row second from the right is Louis Smith.

The third generation (Phil called it ‘The Scattered Generation’) was his own. Phil had 18 cousins. Being the youngest of them all, Phil was the only one not born in Wandiligong. His brother, Don was born there in 1921, but he was born in Footscray in 1928. His parents had left the town in 1922 for improved work opportunities, and Walter quickly found employment as an engineer driver in Footscray. Phil grew up in their home in Chirnside Street in Footscray. This was the same house that my siblings and I were raised in our early years.

The gold-mining town of Wandiligong c. 1870. Thomas and Frances arrived there about 7 years prior to this time.

Phil was also, in his family, the last cousin standing. His parents, Walter and Frances Smith (nee Taylor) had married late, the principal reason being Walter’s desire to support his mother for as long as he could before travelling to Europe to participate in World War 1. Consequently, he married late, returned to Australia in 1919, and began his family with his war-widow bride, Edith, late.

Phil’s brother died in 1988. His last cousin, Rex Smith died 20 years prior to his passing in 2016. He had known all of his Wandiligong uncles and aunties, and all of his cousins. He knew that if he didn’t tell the family story, no-one could. And so he did.

Phil never saw his book published. In the last year of his life and as his health began to decline, I sat with him in his study to help him complete the draft. I did nothing with his script because it was finished, but he had an enormous file of uncaptioned and frequently unscanned photographs which had to be dealt with. Frankly, this task, and that of placing them in the text, was beyond him. It was my pleasure to work with my father to do the work required to sort, caption and place those photographs to complete his draft.

Phil gathered a lot of information about his family's early days in Australia from a set of letters he called 'The Durham Letters'. These form much of the correspondence between Thomas and Frances Smith and their family in England.

The final thing we did was to write a script for the back cover of his book. This was only about two weeks before his death. He was sitting at the kitchen table, and he was too tired to walk to the computer in his study to do this task. From memory, it was the morning of the afternoon Helen and I took him to his Mt. Waverley doctor, which in turn saw us take him to Cabrini Hospital, a place he did not leave.

Because he wasn’t able to come to the study, he gave me an outline of what he wanted, and I typed and printed it for him. I read it to him at the kitchen table and commented on it. We did this several times as I went back and forth between him and the study until it read as he wished it to. And his book was finished.

Phil died at Cabrini Hospital on September the first, 2016. He died surrounded by his family, many members of which had camped in his hospital room for the previous few days. His granddaughter Hannah, who was living and working in Toronto, Canada, flew back to be with him. She made it by an hour or so.

I spent the following year pulling Phil’s picture and text files together, and tying up loose ends before The Blacksmith’s Family could go to print.

The cover of Phil Smith's The Blacksmith's Family. This is Thomas Smith's blacksmith's shop c. 1895. Thomas is leaning against the pole. His son, Louis is standing by a horse that he is shoeing. Following Thomas' death in 1903, Louis took over the shop.

On one level, The Blacksmith’s Family is just one of many family histories to be published. But on another, it is an Australian history book. The lives of three generations of Phil’s family members play out against a background of many of the most significant events that shaped the second half of the nineteenth century and the first half of the twentieth. These include British emigration to the colonies, the 1850s and 1860s goldrush and its explosive impact on Victoria’s economy, the creation of an Australian nation through the federation of its states, World War 1, and World War 2.

It is a great shame that Phil did not see his book in its published form, but he died knowing that it would be published. He lived a full, loved and loving life. As well as experiencing a solid dose of tragedy and loss, he experienced more than his fair share of laughter, joy and happiness. Not a bad effort for a blacksmith’s grandson.

One of his dozens and dozens of sayings (my sister has the list and it’s growing all the time) was “Share the wealth”. It has stayed with me. What a gift.

Phil Smith in Wandiligong in 2008. He's standing outside the former home of his uncle, Louis Smith.

*Should any reader want a copy of The Blacksmith’s Family, they can contact me via the ‘Contact’ page.